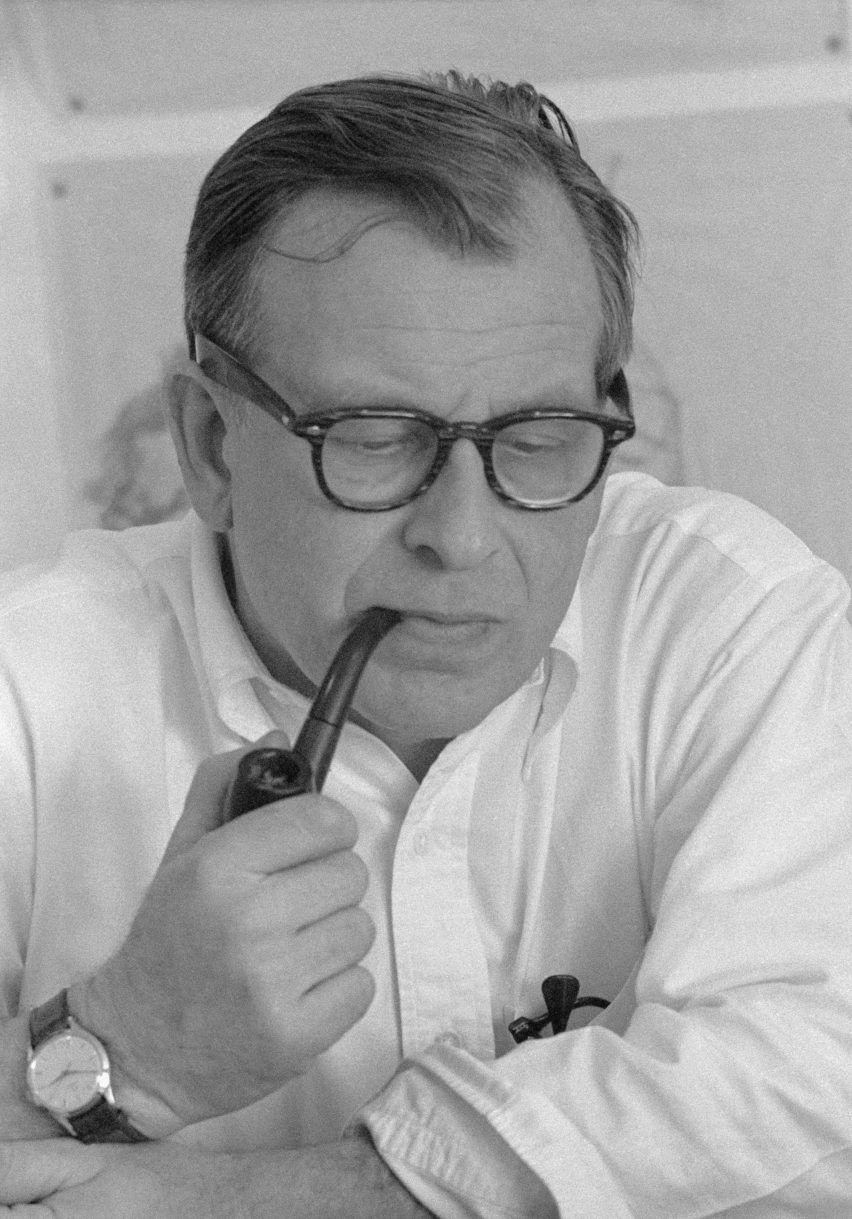

We continue our series on mid-century modern design with a profile of Eero Saarinen, the Finnish-American architect and industrial designer whose creations were embraced as optimistic symbols of a new postwar era.

“We have chairs with four legs, with three and even with two, but no one has made one with just one leg, so that’s what we’ll do,” Eero Saarinen told his friend, designer Florence Knoll, before a new design project.

With this, the Tulip Chair’s iconic wine glass shape was born, a design that, along with the tall concrete wings of the TWA Flight Center, would become synonymous with the design of the so-called “American Century.”

Labeled everything from organic and space-age to neo-futurist and proto-postmodernist, critics have had difficulty assigning Eero Saarinen to a particular style, his work being defined by his constant revision and experimentation.

Eero Saarinen wanted to break away from the strict rules of European modernism, which he called “the measly ABC,” according to curator and historian Donald Albrecht’s book about the designer, Shaping the Future.

He aimed to demonstrate that the old mantra “form follows function” didn’t just mean building orthogonal boxes – or four-legged chairs.

Eero Saarinen started creating at a young age

Born in 1910 in Kirkkonummi, Finland, to architect Eliel Saarinen and textile artist and sculptor Loja Gesellius, Eero and his sister Pipsan grew up immersed in their parents’ professional world.

“By the time Eero was five years old, his talent for drawing had already shown itself,” said a 1956 TIME magazine article. “Sitting under his father’s drawing tables, he actively produced his own versions of door and house details. .”

Eero Saarinen was 13 years old when his family emigrated to the USA. They settled in Bloomhill Fields, Michigan, where publisher George Booth invited Eliel Saarinen to design a new education, research, and public museum complex – the Cranbrook Educational Community.

True to his tradition, Eliel Saarinen enlisted the rest of the family for this endeavor, with Pipsan contributing decorative details and Loja creating personalized fabrics.

Young Eero Saarinen, who began studying what historian Tracy Campbell called his “first love” of sculpture at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, was tasked with designing a line of furniture for the campus.

The designer followed in his father’s footsteps

His art deco pieces were based on traditional Scandinavian design, and Booth even agreed to allow Eero Saarinen to license them, effectively giving him his first industrial design contract when he was still just 19 years old.

This burgeoning career in furniture design was postponed, however, in favor of architecture, with Eero Saarinen later recounting how “it never occurred to me to do anything other than follow in my father’s footsteps”.

In 1931, he went to Yale to study architecture and received a scholarship that allowed him to travel through Europe and North Africa after his graduation in 1934.

After his travels, Eero Saarinen returned to Michigan, working alongside his father in both his architectural firm and the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Here, Eero Saarinen would meet designer Charles Eames, whom Eliel Saarinen named head of the school’s industrial design department, and his initial interest in furniture design would gain a new outlet.

Eames collaboration resulted in molded plywood chair

Eero Saarinen and Eames teamed up to enter the New York Museum of Modern Art’s Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition.

Although their winning design – a chair made from molded plywood aptly called the Organic Chair – proved very difficult to manufacture at the time, it would act as a prototype for what would become an extremely recognizable element in both designers’ later work. .

Shortly afterwards, in 1943, Florence Schust, a long-time close friend of the Saarinen family, would join Hans G Knoll’s company, and the two were married three years later.

At Knoll Associates, Florence Knoll was instrumental in bringing many architects’ furniture designs to market.

It was his task to Eero Saarinen to create a chair “like a big basket of pillows that I could snuggle into”, which led to the Womb Chair in 1948, an armchair that envelops the seated person with a deep, molded shell of fiberglass covered in filling.

Eero Saarinen wanted to clarify the “legs slum”

Experimentation with these materials and shapes continued, and Eero Saarinen became known for working on hundreds of models and prototypes to find perfect curves and proportions.

This culminated in 1958 when he debuted the One-Legged Pedestal series, including what would later be known as the Tulip Chair and Tulip Table.

“I want to clear the slum of the legs,” he said of his simplified design, “I wanted to make the chair one thing again.”

Although Eero Saarinen’s early work in architecture was often guided by his father’s more traditionally modernist approach, he soon began to bring the level of experimentation found in his furniture designs to an entirely new scale.

His breakthrough as an architect came in 1948, when he defeated his father and the Eames Office to win first place in the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Competition in St Louis, Missouri, proposing the now-iconic Gateway Arch.

Described by architecture critic David Dillon as a symbol of “boundless American optimism,” this 192-foot-tall stainless steel arch would become the tallest in the world when it opened in 1964.

When Eliel Saarinen died in 1950, Eero Saarinen took over the firm and, over the next decade, quickly became the architect of choice for corporate clients.

The first high-profile client was General Motors, for which Eero Saarinen would design the Technical Center campus, including a vaulted showroom and open-plan offices illuminated by luminous grid ceilings.

In the same year, he was also appointed to design the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport in New York, which was intended to capture what he described as the “feeling of flying” in its concrete roof structure and fluid, streamlined interiors.

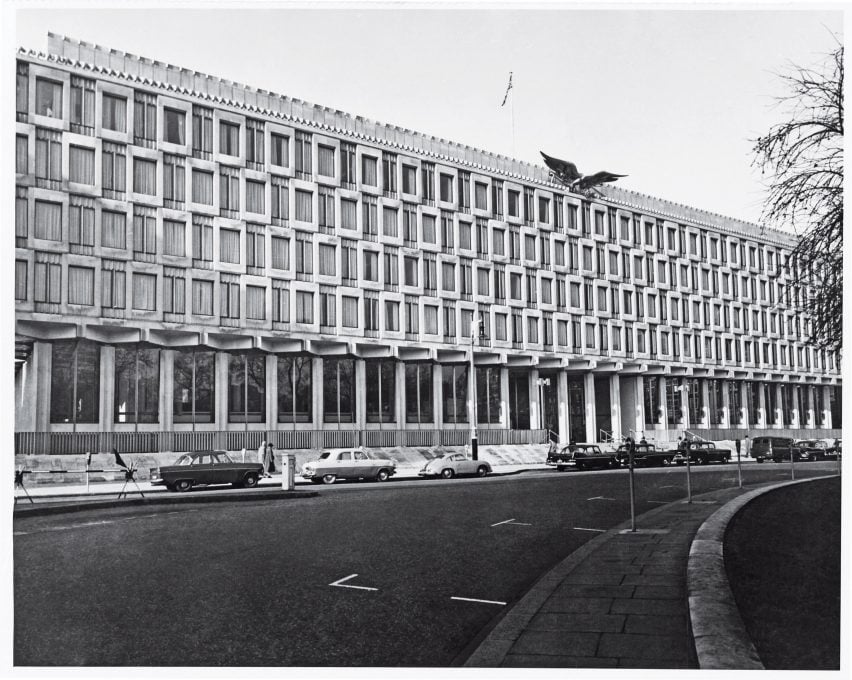

For IBM Computers, the company made a lightweight orthogonal structure clad in vibrant blue glass—the thinnest exterior wall in the world at the time—and for the CBS broadcast network, the company would design its only skyscraper in Manhattan.

Eero Saarinen’s designs incorporated interiors and furniture

Echoing the “total design” approach that echoed his father’s earlier work at Cranbrook, Eero Saarinen often devoted attention to interiors, introducing dramatic staircase lobbies as well as furniture made by himself and his colleagues that challenged typical modernist office design. .

The Model 71 and Model 72 or “Executive Chair” series, for example—a toned-down version of their more dynamic plastic designs—are designed to look as comfortable in a corporate office conference room as they do in a modern setting. living room.

Eero Saarinen’s lack of a signature style and constant experimentation probably contributed to making him so attractive to commercial clients interested in creating a good impression, but it led to a mixed critical reception from architectural circles.

“The criticism was about the variety of his work, each client receiving a different form, technology or material,” historian Albrecht told Dezeen.

“In the Mies era, this meant that Saarinen was pleasing every client and had no style of his own,” he added.

Despite his company’s rapid backlog of work, some of Eero Saarinen’s most famous projects – including the Gateway Arch and the TWA Flight Center – were ones he would never live to see completed.

In 1961, he died at age 51 while undergoing a brain tumor operation in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Eero Saarinen would posthumously receive the AIA Gold Medal a year after his death in 1962, but even long after his death, his work would continue to be ignored by critics.

It was only in the 1990s, when a new era of iconic form-making and renewed interest in technology began, that many re-evaluated just how prescient Eero Saarinen had been three decades earlier.

The main illustration is by Vesa S.

Mid-Century Modern

This article is part of Dezeen’s mid-century modern design series, which looks at the enduring presence of mid-century modern design, profiles its most iconic architects and designers, and explores how the style is developing in the 21st century .

This series was created in partnership with Made – a UK furniture retailer that aims to bring ambitious design at affordable prices, with the aim of making every home as original as the people who live in it. Elevate everyday life with collections made to last, available to shop now at made.com.

#Eero #Saarinens #designs #measly #ABC #modernism